Cat among the Pigeons – sample

‘What’s that you’re reading?’ I stand the paperback up for him to see the cover. ‘Pathfinders, Air Vice-Marshal … Bennet. Any good?’

‘You should know. You lent it to me.’

‘Oh yeah. Course I did. Any good?’

Wads is losing his memory: definitely going. Harry Waddington: tall and broad shouldered, hair almost completely white, now, onetime chief draughtsman in the jig and tool drawing office, AVRO Yeadon, designing Ansons and Lancasters. Four years older than me and technically my boss, but we always got on well and have been friends ever since the war. Very sad it is to see him in this state aged seventy-three. To think he was one of the people who persuaded me to sell the house last autumn and move in here. How the blazes I hadn’t realized how far downhill he had gone, I can’t imagine. Fact is, I’m stuck here in The Cedars residential home, practically deaf in one ear, one leg shorter than the other and a hip joint knackered: fine mess and no mistake.

There’s George, of course. He’s still with it, all right. Good chess player–usually beats me, at any rate–but apart from moaning about Margaret Thatcher’s government, he doesn’t have much to say. Worked most of his life for the Coal Board. Then there’s Ivy and her friend Gwen. We have a laugh, you know. But, apart from that, nothing much. I feel old before my time in here. I have a bit of a joke with Jane, on the staff, but she’s too busy to talk for more than two or three minutes at a time.

And me: Fred Catterall, a bit above average height. Not bad looking, for sixty-nine, most of my own teeth and a good head of hair, though I keep it short. Was black‒mostly grey now. What makes me seem older than my years is that I can’t get about properly. Slowed down a lot with this damned hip joint playing up. Hardly the ladies’ man in this state. There aren’t going to be any more women. No–not that I’d mind one or two–still, stuck in this place, it’s not going to happen, is it? It’s just not going to happen. Two marriages and nothing to show for it but my weakling son Richard over in Beverley and his selfish bitch of a wife Sharon, who’s waiting for me to pop off. No sign of any grandchildren. When I think of how different things could have turned out …

* * *

George and I can come and go as we please, so long as the staff know where we’re going and what time to expect us back, but it’s got now that Wads has to be with someone: usually one or both of us. I often go with George and Wads to buy the papers and the odd magazine for Gwen and Ivy. We’ll maybe call in at the Albion for a pint on the way back. Not today, though. It’s cold and damp and I’m better off just sitting here in the warm, with my book. I never seem to get tired of reading about the war in the air … I often wonder what I’d have ended up doing if I’d been called up. One thing I’ve noticed is that the blokes who were sent overseas mostly don’t want to hear any more about it, like George. Wads and I were in a reserved occupation at AVRO: probably saved our lives, or at least, saved us from having a bad time. We were lucky.

The others are late back. The rest of us are half-way through the soup when they blow in and plonk themselves down, George next to me and Wads opposite: we all have our set places.

‘We got talking to Bert and his brother what’s-his-name in the pub and had another round.’ By Wads’ flushed face and his voice‒even louder than usual‒it looks as if they’ve had more like two or three more. George is supposed to keep an eye on him, what with his diabetes. Sometimes they’re as daft as each other. But anyway …

Wads picks up his soupspoon and points it at me.

‘We bumped into Esther, too, on the way back …’ George cuts him short:

‘It was Mrs Hargreaves, Harry. You’re getting muddled.’ So I step in:

‘They do look a bit alike, it’s true, now I come to think of it.’ But Wads isn’t having it.

‘I don’t know why she doesn’t move in here with you, Cat. She’d be better off ’n being on her own. Still, it’s a nice place you’ve got. I’m not saying it isn’t.’

Their two plates of soup arrive, which puts an end to that conversation. Just as well! Mrs Hargreaves is in charge of the cleaning staff. Fancy him thinking she was my wife–my first wife, that is–when she’s been gone these twenty years! But he remembers her all right. What goes on in his head? I wish I knew.

* * *

Wads hasn’t mentioned Esther again. I’m hoping it was just a one-off. The day after the drinking episode he had a bit of a blackout and an ambulance came to take him to the infirmary for tests. They didn’t keep him in, though, so that was a good sign, I suppose. He’s probably forgotten all about it. Anyway, he hasn’t gone off the rails since.

Monday morning: he and George have gone out for the papers again, and here I am sitting looking out of the window. I’ll probably have coffee with Gwen and Ivy, when it comes round. No sign of Gwen for the moment. Ivy’s sitting over the far side of the lounge listening to another woman I don’t really know, who never stops talking. She occasionally glances over in my direction. She knows it’s me, but I don’t think she can see me very well from that distance‒it’s a big room‒without her glasses. The daffodils are well on and the tulips should be in flower in a week or so. They keep the garden nice. I’m watching a couple of blue tits swinging about, pecking at some pieces of coconut hanging on a wire from a flowering cherry tree just outside the window. Bit of ground mist on the lawn, then the two dark cedars practically hiding the main house. Must have been quite an estate before they built this place. Vanished world. The upkeep must have been tremendous.

I like mornings like this. The end of the afternoon before tea is the time I dread most. The television’s on in the other room, but I only watch it a bit in the evenings, sometimes. Some of them even watch Children’s Hour. I don’t think they even know what’s on the screen. Then there’s the oldies. They just sit in their chairs, day in, day out, in a row against the back wall of the lounge. They don’t talk to each other. They just sit there like pigeons on a window-ledge: oblivious.

I turn my head and see the smart, if a bit plump, manageress coming quietly across the lounge to where I’m sitting.

‘Morning, Mrs Scott.’

‘Good morning, Mr Catterall.’ Then she says something I don’t catch.

‘Beg pardon?’

‘I say: there’s a young lady to see you.’

‘To see me? Who is it? Sharon? What can she be wanting?’

‘No. It’s not your daughter-in-law. A certain Miss Sophie Beale. Shall I show her in?’

‘Well, I’m blowed if I know who she is. Anyway, better show her in, I suppose.’ Mrs Scott turns and trots off towards the reception. I run my fingers through my hair and get hold of the handle of my stick, ready to stand up.

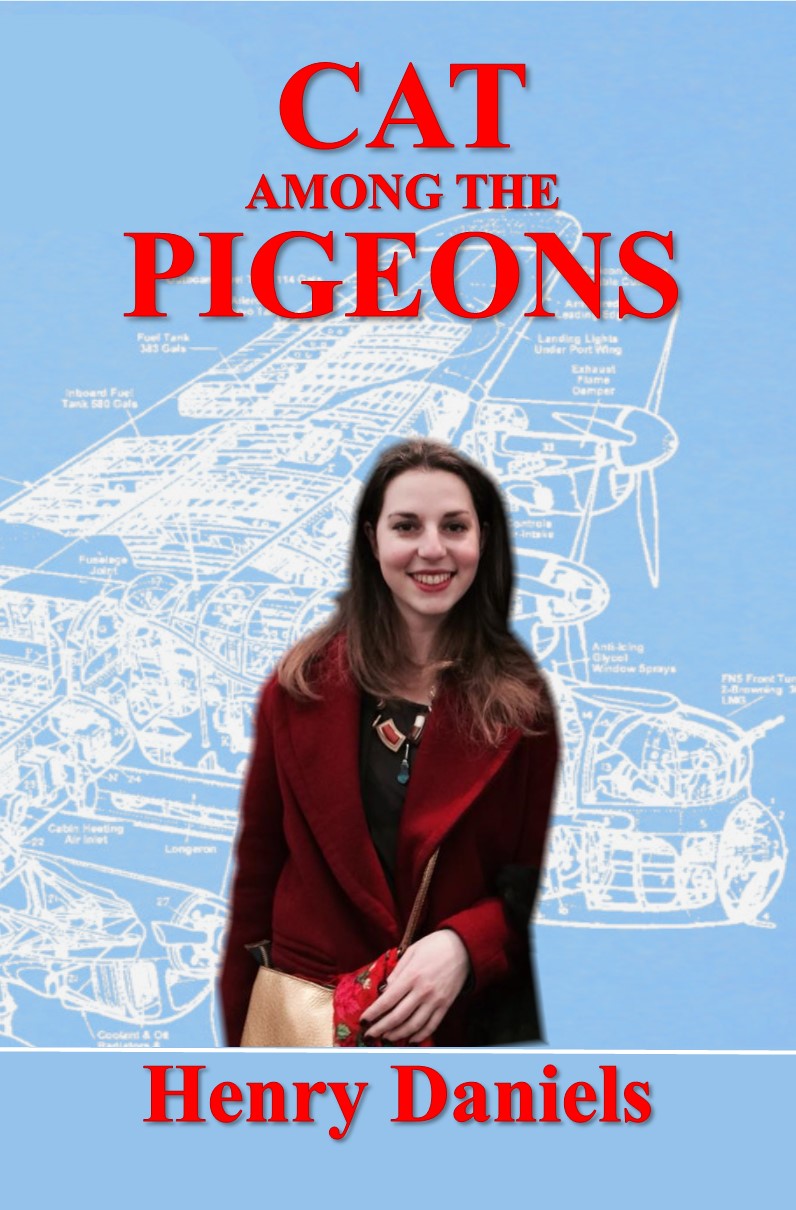

After a minute, Mrs Scott reappears, followed by a fairly tall, slim girl with longish, brown, slightly wavy hair, wearing a dark red coat with a belt loosely knotted at the waist, dressing-gown style, a handbag hanging from one shoulder and carrying a little attaché case on the other side. As she comes nearer, I get a better view of her: early twenties, brown eyes and tastefully made up. I’d say she was from a bank or an insurance company. Some sort of representative, but very nice to look at. I get up, feeling the usual shot of pain down my thigh.

She introduces herself as Sophie Beale. Quickly pulling off a black leather glove, she holds out a fine, white hand, which I take in mine. She doesn’t actually shake my hand, just squeezes it slightly, looking me straight in the eye.

‘How do you do, Mr Catterall!’

‘How do you do!’ Mrs Scott steps back:

‘So. I’ll leave you to it. I’ll draw up another chair for you.’ She turns my chair round so that it’s three quarters facing the window, then draws up another in front of it. Miss Beale thanks her. I nod.

‘Jane will be round with the trolley in a minute or two. You’ll have a cup of coffee or tea, Miss Beale?’

‘Why, thank you! That’s real nice of you, if it’s not too much trouble.’

‘No trouble at all.’ She smiles and leaves us. Miss Beale puts her handbag and attaché case on the carpet and takes off her coat, which she drapes over the arm of her chair. We sit down. She’s wearing a cream, long sleeved, flannelette blouse, buttoned at the cuffs, a sort of mottled silk scarf, a long black skirt and matching boots: all very elegant. She smiles, showing her teeth, so I smile back.

‘So. What can I do for you, Miss Beale? Not often I get a young lady visitor.’

‘Ah.’

‘Well, I mean we don’t see many young faces in here, apart from the staff. We get a concert now and again, but the lady singers in the choir are mostly … erm … getting on.’ She smiles again, cocking her head slightly to one side and flicking her hair back from her forehead. Nice looking girl. Very nice. I wonder what she wants? She sounds like an American, or maybe there’s a bit of Irish. I’m not much good at accents. As if she’s reading my thoughts, she says:

‘I guess you’re wondering why I’m here, Mr Catterall.’

‘Well, I suppose you’re going to tell me. You haven’t just called in for coffee and biscuits, I imagine.’ She gives a little laugh and seems a bit hesitant–not like someone who’s hoping to sell me something.

‘I’m over here from Montreal. That’s where my home is.’

‘Ah. Canadian. I thought you might be American.’

‘No. Canadian. Erm … I’ll come straight to the point. I’ve just completed …’ She says something I don’t hear properly.

‘Beg pardon? I’m a bit hard of hearing.’ She starts again:

‘I’ve just finished my degree in history. Well, last summer.’

‘Oh! A degree in history. Congratulations!’

‘Thank you. Erm … Yes. So I enrolled for an M.A. in September.’

‘Very nice.’

‘It’s partly a taught course and there’s a dissertation.’

‘Yeah?’ I wonder what that could possibly have to do with me?

‘And … erm …’ She shifts in her chair and though she has her back to the light, I think she’s colouring up a bit. ‘Yes. A dissertation. And as I’m interested in Anglo-Canadian relations in World War Two, I’ve chosen as my subject something about aircraft production … erm … (some words I don’t catch) … principally, Lancaster bombers.’

‘You’re interested in Lancasters?’

‘Yes. Not so much the technical side, or the flying. Really, it’s the people who built them. I know about AVRO in Yeadon, just near here. I’m a social … well … I hope to become … a social historian.’

‘A social historian … I see. It’s a bit strange to think that AVRO counts as history. Doesn’t make me feel any younger!’ I glance around the room. Gwen has come in without my noticing and has sat down with her back to me opposite Ivy, who has put down her magazine and is looking over towards where this young lady and I are sitting. She ought to be able to see us all right with her glasses on, but you never know with women, do you? Born in Hunslet, was Ivy. She and Gwen often come over to the window for morning coffee, but not today, apparently.

Miss Beale asks me a few questions about my time at AVRO. She seems interested in the way we were able to put completely unskilled people, mostly conscripts, on medium precision jobs by making drawings for very single operation. That’s how it worked. Course, in the drawing office we were a sort of élite–I made that clear to her–not top brass, but not on the factory floor, either. We were away from the noise and the dirt most of the time. Anyway, she’s lapping it up.

‘The real blue-eyed boys were the test- and ferry-pilots.’

They never had any problem finding female company, if they wanted it. A lot of the women were rough, though. Cheery, mostly, but rough. They’d cheek you off soon as look at you. And the language! I never heard women use that kind of language before or since! I’m wondering whether I should mention any of this to Miss Beale. She’s only young and looks a bit genteel to me. Better just give her the general outline for the time being.

Jane comes through into the lounge, pushing her trolley, cups and saucers rattling. She goes straight over to the far corner and works her way back, as she generally does. Good sort, Jane. Funny, me just mentioning blue-eyed boys, ’cos she’ll often come up to me with her trolley and she’ll say: ‘An’ how’s my blue-eyed boy this morning?’ and I’ll say something like: ‘All the better for being served tea and biscuits by the lovely Jane Russell!’ She has the dark hair, all right, but not the figure‒and she must be a good six inches shorter than the original. It’s just a way we have. No harm in it. Mrs Scott always calls us residents all by our surnames, but Jane and most of the others call us by our first names, so I’m Fred, George is George and Wads is Harry.

Today it’s just a quick ‘Mornin’. Miss Beale and I each get our coffee in the usual pale green cup and saucer with a couple of biscuits on the usual little pale green plate. Jane then pushes her trolley over to the three old dears who always sit together by the door, keeping an eye on who comes and goes.

‘It’s only instant coffee, I’m afraid. The biscuits are all right though: Rich Tea. I don’t know if you have them in Canada … Where did you say your home was?’

‘Montreal. The coffee’s fine. I’m ready for a drink. I was up early this morning.’

‘Did you fly into Yeadon? Leeds-Bradford, it is. Known locally as “Yeadon Airport”.’

‘No. I came into Heathrow, got the train up to Leeds yesterday morning, then hired a car and went to see someone I’d arranged to meet at the University. Everything is so close together in England.’

‘Must seem tiny after Canada: wide open spaces and the Hudson River and what have you!’

‘It sure does. I like what I’ve seen so far, though. It’s kind of sweet: nice feel to it.’

We sip our coffee. She turns her head to the window, pushing her hair back from her face and I get her profile. She has a lovely, slim neck and delicate, nicely-shaped ears.

‘Real nice garden. I guess you all sit out as soon as the nice weather comes? What lovely trees!’

‘Cedars–hence the name. It’s the name of the big house further up the drive. We’re sitting in what used to be their front garden. They sold off the land ten or twelve years back.’

‘It’s very well-appointed: very spacious.’

‘Purpose-built. I only moved in in the autumn. So I haven’t had a chance to sit out in the garden yet.’

She turns back to face me. What’s all this leading up to, really? I wonder if this research story’s true? We’ll see. Meantime, I can’t say it’s unpleasant having my morning coffee with this smart young lady from Montreal. I take a quick glance over to the far end of the lounge. Gwen and Ivy are drinking their coffee. Not showing any signs of coming over to join us. Makes me feel a bit uneasy, somehow. Still, I didn’t know I was going to have a visitor, did I? Ivy glances over this way. She knows it’s me well enough. Course she does!

‘Did you work in artificial light all over the factory, Mr Catterall? Were there no windows?’

‘No. It would have been too dangerous: risk of making the place visible from the air, if someone forgot about the blackout. All the assembly departments and stores were lit by mercury vapour lights in banks: thousands of them, and most benches had their own angle-poise lamps so the machinists could see what they were doing. In the drawing-office we had fluorescent tube lighting. Each draughtsman worked on his own at a long table, so there was no chatting. We used to get headaches. Mind you, the worst was the spray shop, alias the ‘dope house’, the girls who worked in there had permanent headaches and sickness from the fumes. Very unhealthy. They had to seal all the seams on the airframes with red lead paint and spray all the assemblies with amyl-acetate. They were given two pints of milk and an Adelexin tablet to take every day. Rotten job, but a lot of them stuck at it. They got extra money, you see …’

‘I guess conditions were pretty bad for everybody.’

‘Not as bad as you might think. There was a … now … what was it called? … a Prod … Joint Production Committee, that tried to maintain minimum comfort for everybody. It was the long hours and the travelling that wore people out as much as the actual work. I was lucky, living in Guiseley, just a few miles away. They had a fleet of special buses ferrying people to and from the place, but some people had an hour or more travelling before and after the shift. A lot of people‒the blokes in particular‒hardly ever saw their families. Mind you, women usually got a bit of time off if their husbands were on special leave from the forces. It wasn’t a slave camp, or anything, and we had music broadcast over the Tannoy. “Music While You Work” on the BBC. It helped to pass the time on. Course, it was supposed to make everybody work more efficiently. Whether it did or not, I couldn’t tell you. But it helped take people’s minds off the war. Didn’t do any harm, anyway.’

‘And there were trades unions, I imagine?’

‘Oh, goodness, yes. There were lots of them.’

‘And did everybody have to belong to one?’

‘No. It wasn’t a closed shop …’ Miss Beale’s looking at me very intently and has put her cup and saucer down on the little table between us, ‘Erm … don’t forget your coffee, love … Miss Beale. Do you want it filling up? I can call Jane back. She’ll give you a drop more.’

‘No. Please. One cup is enough. It’s fascinating hearing all you have to say.’

‘Well! It’s nice to have someone who’s interested! Most people of your age have never even heard of AVRO. Folk round here, I mean … Let alone people in Canada. I can’t get over how you come to be so interested … I mean … how you chose AVRO as your … topic, like.’

She quotes some figures.

‘Sorry. I didn’t catch what you said.’

‘I said: Two thousand, eight hundred eighty-two Ansons were built in Canada.’

‘Is that a fact? I know a good number were made over there, but …’

‘And eight thousand one hundred thirty-eight in the UK. Half of them were built in Yeadon.’ Well, now!

‘I can see you’ve done your homework. This is a turn up for the books! Who’d have thought I was going to meet you today, telling me about production figures at AVRO? It hardly seems possible!’ I’ll swear she’s enjoying this, the way she’s beaming at me. Wait till Wads comes in! He’ll never believe it! ‘But … How did you know I’d been at AVRO and–more to the point–how did you know where to find me? You know about Harry Waddington, too?’

‘Harry Waddington?’

‘If you know about me, you must know about him. He was my boss.’ She’s going a bit pink. I knew it! There’s something not straight about her. She’s going to try and get some money out of me. I can see it coming. ‘Tell me how you found me and how you knew I was at AVRO. I left there long before you were born.’

‘I know you did. You were hoping to stay on, but when they closed the factory down, you set up on your own: West Yorks Engineering.’

‘Well I’m blowed! Who told you that? Mrs Scott?’

‘No. Not Mrs Scott. I’ve known it for quite some time.’ She’s smiling all over her face.

‘I get it: so you’ve traced some of the personnel from AVRO and found out what you could about them and now you’ve come over to meet them and get some first-hand stories for your research. That it?’

‘Well, it isn’t difficult to trace people with the international telephone exchange.’

‘But the names? How did you get the names in the first place?’

‘Ah!’ She looks down at her coffee cup.

There’s a bit of a draught this side of the lounge every time the outside door in the reception opens. I turn my head. Sure enough, it’s George and Wads back from the paper shop. They breeze in through the glass doors with Jane behind them, pushing her trolley. George sees I’m with someone, and drops back, but Wads comes straight over.

‘Well, well! Soon as our backs are turned! Trust Cat to find himself a young lady to talk to!’

Miss Beale stands up straight away. I follow suit, but more slowly.

‘Wads, this is Miss Beale … erm … Harry Waddington.’ She holds out her hand:

‘How do you do. I’m Sophie Beale.’

‘Over from Montreal, Wads.’

‘How do! You from the press? Interviewing young Cat, here?’ She smiles and glances sideways at me:

‘In a way, yes. Not the press, though. Heaven forbid!’ I break in:

‘Draw up a chair, Wads. You’re going to like this. Miss Beale here is doing research about AVRO.’ Jane pulls up a chair for him, puts a cup of coffee and a little plate of biscuits on the table next to him, looks at the three of us with a little smile as we sit down, and wheels her trolley over to where the oldies are sitting against the back wall. George has wandered over to sit with Gwen and Ivy with their magazines.

‘Bit blustery out.’ Wads rubs his hands together, still with his coat on, ‘Not what you might call spring weather, yet. ‘Where did you say you were from, Miss …’

‘Beale. Sophie Beale.’

‘She’s come over ’specially from Montreal.’ Wads looks blank. ‘Montreal in Canada.’

‘Canada! That’s a long way to come. Fly?’

‘Yes.’

‘And what was it you just said about AVRO? You used to work there? I don’t remember the name …’ Oh Wads! I step in:

‘This is the Harry Waddington I was telling you about: chief draughtsman–my boss at AVRO.’

‘It’s sure nice to meet you, Mr Waddington … or maybe I should be saying Doctor Waddington?’

‘No, no. Just plain Mr. I’m not Barnes Wallis or anyone … Have you seen the papers this morning?’

‘No. I’m afraid I haven’t …’

‘Don’t you get a paper?’ I step in again:

‘Wads, Miss Beale’s just flown in from Montreal. She won’t have seen the Yorkshire Post.’ I give her a little wink and she smiles back.

‘So you weren’t actually at AVRO yourself?’

‘No. I wasn’t, but I’m enrolled on a Master’s course in modern history and planning to write my dissertation about the people who were.’

‘I see. Well, you’ve struck lucky. Cat’s your man: wonderful memory. Best draughtsman I ever had, too!’ He reaches for his cup. ‘I’ll tell you one thing, though, the coffee we got during the war was awful stuff. So was the beer: like licorice water with a bit of scum floating on the top. Still, we used to call in sometimes for a couple at the Peacock after work, didn’t we, Cat?’

‘We certainly did.’

‘What’s the Peacock? She looks at me.

‘The Peacock Hotel. Pub … lic house on the Harrogate road, just near AVRO. Everyone–well, those as liked a drink–used to go in there. It was the nearest pub. Quite a classy building. Put up in the thirties.’ Miss Beale looks interested.

‘Is it still standing?’ Wads replies confidently:

‘Was still there, last time I was in Yeadon. Mind you, that would be … a while back, now. It’ll still be where it was. No reason why it shouldn’t be, is there, Cat?’

‘Well, no.’ Miss Beale is loving this:

‘That is interesting! I’d kind of like to see it!’

A bit more chat about AVRO. She’s already swatted up quite a bit about the place, which impresses us. Here’s this young girl, turned up out of the blue, telling us things we haven’t heard anyone mention for‒what‒forty years! Thing is, so many people left the area when the factory closed down, people we lost contact with, it’s like a place sealed off in time. We can never live those days again, or anything like them, and yet she’s bringing it all back to life! She wants to know names of people and their jobs, the colour of their overalls, what the food was like they dished up in the canteen and, not least, what music they broadcast over the Tannoy. Well, that’s an easy one! She gets this notepad out of her bag and a biro, and as fast as we can reel off the titles and the names of the bands she scribbles them down. She’s familiar with a lot of them, but when we come up with one she doesn’t know, she’s delighted. Talk about a carry on! Wads and me are like a couple of youngsters! She doesn’t realize these swing numbers remind us of our courting days–girlfriends who came and went–and for me the first years of being married to Esther and our Amy being born! Funny how little it takes to make you feel young again: just somebody taking an interest is enough to set you going. Course, Wads being a bit older, some of his favourites aren’t the same as mine. Between us, I reckon we’ve come up with a good fifteen or twenty hit songs, and down they go on her notepad.

We could go on all day, but come half eleven or so she says she has to go over to have lunch with someone from the University. That’s a bit of a let-down. When she gets up to go, Wads helps her on with her coat‒always the gentleman‒and as she reaches to pick up her gloves from the table, I notice again how fine and delicate her hands are. She’s a nicely turned-out girl all right. She promises to come back tomorrow about the same time and will Wads and I have a think about anything else we can tell her about. Well! That shouldn’t be too difficult!

* * *

As usual, Gwen and Ivy sit down to dinner at the same table as George, Wads and me. There was another chap called Leslie who’s had a stroke and is in hospital now. We’ve just heard he won’t be coming back to the Cedars, poor bloke. His people are coming this week to shift his stuff out, so his room will be vacant. Someone’s sure to be coming in, but they haven’t told us who, yet.

Gwen’s her usual self, but Ivy’s not very talkative today. She disappears straight after pudding, but comes back to join us for coffee in the lounge afterwards. She’s taken off her cardigan and put on a bit of lipstick and some pink nail-varnish she wasn’t wearing at breakfast time, if I’m not mistaken. She’s not what you might call a film star, but I like to look at her bare arms and her eyebrows, which are sort of raised and arched most of the time‒Belinda Lee style: bit sexy, in a way. I know that sounds funny: she must be seventy if she’s a day. She moved in here just before me at the end of the summer.

The others go off for a rest or to watch television before the concert later on. She stays put and as soon as there’s just the two of us, she starts up:

‘So! I see you had a visitor this morning. It’s not the usual woman from the bank. Who’s this one?’ She looks at me square on, stroking her chin with the tip of her middle finger and sort of smiling, but not quite.

‘No. Not the bank.’ (I tell people here the girl who comes to see me once a month is from the bank. In fact, she’s from the finance company who handle my investments). ‘Erm … girl doing research about AVRO: the aircraft factory at Yeadon.’

‘I know all about the AVRO, number of times you’ve told us about it, you and Harry.’

‘Yeah, well. Anyway. She’s got this project going. Social History. Over from Canada.’ Ivy relaxes a bit and taps her lips with her forefinger.

‘Not a local girl, then?’

‘No, no.’

‘Very smart, though.’

‘Erm … smart enough, I suppose. Better than average for these days.’

‘And she came to … like … interview you?’

‘Me and Wads. Yeah.’

‘And how did she find you?’

‘Erm … I asked her that. What did she say? Darned if I can remember what she said! There must be records in Canada. A lot of aircraft for us were built over there and Yeadon supplied them with parts: all shipped over. That’s the link-up.’

‘Well, it sounds a funny sort of research for a girl to be doing.’

‘It does, a bit. But it’s the social side she’s interested in: people, you know … what they did … the styles … music: wanted to know all about the dance bands.’

End of this sample – click here to buy it on Amazon (Kindle or paperback editions available)